Today’s blog post is a guest post by my friend and colleague, René Saldaña, Jr. It’s such a treat to host him, his teaching, and his students.

Today’s blog post is a guest post by my friend and colleague, René Saldaña, Jr. It’s such a treat to host him, his teaching, and his students.

First, a bit of background: René Saldaña, Jr., is the author of several books for children and young adults, among them The Jumping Tree, A Good Long Way, Heartbeat of the Soul of the World, and A Mystery Bigger than Big, the 4th installment of his bilingual Mickey Rangel mystery series. In honor of pets and in celebration of Sylvia and Janet's latest Poetry Friday Power Books, Pet Crazy, here is a list of his own: Sadie and Chito (dogs) and Gordon, Cotton, Jet, Dottie, and Raisin (all cats). He is associate professor of Language, Diversity, and Language Studies in the College of Education at Texas Tech University.

First, a bit of background: René Saldaña, Jr., is the author of several books for children and young adults, among them The Jumping Tree, A Good Long Way, Heartbeat of the Soul of the World, and A Mystery Bigger than Big, the 4th installment of his bilingual Mickey Rangel mystery series. In honor of pets and in celebration of Sylvia and Janet's latest Poetry Friday Power Books, Pet Crazy, here is a list of his own: Sadie and Chito (dogs) and Gordon, Cotton, Jet, Dottie, and Raisin (all cats). He is associate professor of Language, Diversity, and Language Studies in the College of Education at Texas Tech University.

Here René writes about the evolution of his teaching and shares (with permission) some of the work his students created this summer. Enjoy!

Don’t Be Fooled: Nothing’s Wasted on the Young

A Meandering Piece by René Saldaña, Jr.

Throughout my six years teaching reading and writing in a secondary language arts classroom in Texas, one of the biggest beefs I had with my students on the whole was that they didn’t pay attention: to me, to instructions, to the world around them. A shame, because if only they had, I would tell them, your writing would be that much better. “All you have to do is to pay attention, observe, just take care to notice stuff.” So much world wasted on the young.

Oh, in my arrogance (I had only just graduated with a masters in literature and boy did I know it all, and way more where my students were concerned!) I refused to give them the benefit of the doubt; instead I pulled a Ruby Payne before Ruby Payne existed as such and sought to blame the kids’ culture of poverty for their lack of willingness to learn. To simply sit back and listen to me teach them what I knew in my heart of hearts would show them how they could defeat this mean and ugly world that had managed to stack every card against them, etc., etc, ad nauseam.

Today, a couple decades and a half later, I don’t “teach” as much as I learn to teach in the moment. I’m trying to take my own advice: to do a lot more paying attention of my own in the classroom, to the personality of this classroom compared to the next and the following and adjusting my approaches, observing the individual student to see what he or she will teach me about teaching, planning for tomorrow only after a long day based on how it went today. I’m more chill today. No less rigorous and my expectations are just as high as before if not more so. But the gray hair has set in on my beard and head, I move slower (or smoother depending on the perspective), I prefer the organic nature of teaching.

Here’s a bit of what I’ve learned.

It wasn’t that they weren’t paying attention; in fact, they were paying very careful attention. It had more to do with my teaching, which is to say, I really wasn’t, teaching that is. I stood in front of the classroom, center stage droning on about one thing or another, expecting them to just get it, and if they didn’t, it had more to do with them and their ill-educated parents who cared little about their children’s academic success than with me. After all, wasn’t it I who showed up every morning ready to teach their children, “on the front lines,” we described it as. I had been one of them, literally: I had graduated from this very district years back, had left for college, left the state, as a matter of fact, made it through a bachelor’s and a master’s. I knew what was best for them. What I didn’t know was how to teach them, how to reach them.

Nowadays, I own that I don’t know jack about teaching, despite years doing it at the secondary and university levels, and in a college of education for the past 10 years no less (don’t believe me? I’ve got the lapel pin to show you if you need proof). I have learned a few things, chief among them, young people do pay attention to me (I like to tell myself this at least), to the instructions I give them (today more about inquiry than passively taking in what I dish out), and to the world around them. They’ve actually been paying very careful attention. All they need to show us how much they have been doing so is to provide for them a venue: and poetry—the reading of it, and the writing of it, especially—is just such a venue.

This past summer, I worked with a group of rural kids from West Texas on their reading and writing skills. You see, they’re supposed to be behind their other Texan counterparts in urban and suburban areas. They’re from little towns like Morton and Whiteface, from farming and ranching families, most of them Mexican American. Most of them multi-generational. Many of them will not leave their small towns. Or maybe they will, and this is one of the hopes for this Upward Bound program I’ve gladly attached myself to. The director tells me, “Dr. Saldaña, you have free reign; teach them something about writing.” He might think this lessens the burden for me. On the contrary, the load is made heavier. If I had a curriculum dictated to me, I would follow it, I could blame it if things went awry, I could empathize with the students if it got boring: “It’s not me, it’s this blasted curriculum.” I’d want to act like the Robin Williams character in Dead Poet’s Society and call for a sort of academic revolution: “All of you, tear that ultra-prescriptive syllabus into shreds.” We’d litter the floor in shorn paper. On my way out the door, kids would jump up on the desk one by one and salute me, “O, Captain, My Captain.” But no, I have to create the syllabus myself, the daily lessons, confer with students to assess their progress. All the things of teaching. It’s a big deal, really. Daunting.

This past summer, I worked with a group of rural kids from West Texas on their reading and writing skills. You see, they’re supposed to be behind their other Texan counterparts in urban and suburban areas. They’re from little towns like Morton and Whiteface, from farming and ranching families, most of them Mexican American. Most of them multi-generational. Many of them will not leave their small towns. Or maybe they will, and this is one of the hopes for this Upward Bound program I’ve gladly attached myself to. The director tells me, “Dr. Saldaña, you have free reign; teach them something about writing.” He might think this lessens the burden for me. On the contrary, the load is made heavier. If I had a curriculum dictated to me, I would follow it, I could blame it if things went awry, I could empathize with the students if it got boring: “It’s not me, it’s this blasted curriculum.” I’d want to act like the Robin Williams character in Dead Poet’s Society and call for a sort of academic revolution: “All of you, tear that ultra-prescriptive syllabus into shreds.” We’d litter the floor in shorn paper. On my way out the door, kids would jump up on the desk one by one and salute me, “O, Captain, My Captain.” But no, I have to create the syllabus myself, the daily lessons, confer with students to assess their progress. All the things of teaching. It’s a big deal, really. Daunting.

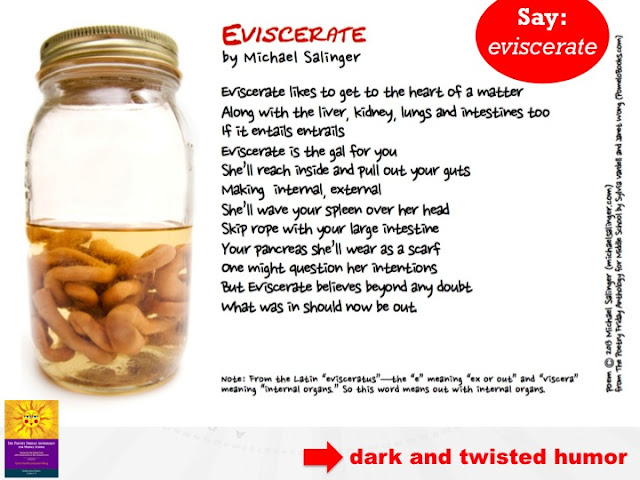

So this summer I went with poetry. I’d only recently read Sylvia and Janet’s Here We Go, their second in the Poetry Friday Power Book series, not quite how-to books but rather experience-doing-poetry books, first hand. I also planned a culminating assignment: they were to perform one original piece at the end of our time together. This was the scarier part for a good many of the students, some thirty in all. We read from the book, we did from the book, I read aloud the work of Josephine Cásarez, a beautiful San Antonio poet whose work demands it be performed (“Up Against the Wall” (1993) and “Me, Pepa Makes It Big” (1995)), we deconstructed what I think is one of history’s best haiku, “A Leaf Falls” by e.e. cummings, and we studied found poems and Golden Shovel poems, and more. Then we drafted and revised, workshopped, revised some more, and finally concluded with two days of performance.

So this summer I went with poetry. I’d only recently read Sylvia and Janet’s Here We Go, their second in the Poetry Friday Power Book series, not quite how-to books but rather experience-doing-poetry books, first hand. I also planned a culminating assignment: they were to perform one original piece at the end of our time together. This was the scarier part for a good many of the students, some thirty in all. We read from the book, we did from the book, I read aloud the work of Josephine Cásarez, a beautiful San Antonio poet whose work demands it be performed (“Up Against the Wall” (1993) and “Me, Pepa Makes It Big” (1995)), we deconstructed what I think is one of history’s best haiku, “A Leaf Falls” by e.e. cummings, and we studied found poems and Golden Shovel poems, and more. Then we drafted and revised, workshopped, revised some more, and finally concluded with two days of performance.

We set up the cafeteria at South Plains College in Levelland (TX) for the readings, and each poet came up with poem in hand and read, while the rest of us sat back and enjoyed. They wanted to snap fingers instead of clap because isn’t that how we should react to poetry? One poet wrote a piece about the day her mother died in a violent car accident. The poet had been in the car, and last thing she remembers is her mother there, then when she comes to, the mother gone literally, but also gone-gone, if you get my meaning, and hers. The audience didn’t know how to react. Not a single one of them snapped a finger for her. They were stunned at her bravery to read such a personal poem. Her voice had even quavered at just the right places. I knew the truth: she’d made up that part about the mother dying. She’d started with truth, then veered, dramatically, traumatically, created a persona, and wrote a moving quasi-apostrophe. The audience was relieved to hear my explanation. They were glad at the news, but still couldn’t find it in them to give her a hearty round of snaps. Somehow that worked better.

Following is a sampling of their work:

Thank you, René, Lily, Jasmine, Cynthia, Martha, and Marisol. How lovely to spend some time with you and your summer writing. Your hearts shine through your poems! Please keep writing….

Now, look for more Poetry Friday sharing at Radio, Rhythm, & Rhyme where Matt is hosting our party and launching his own wonderful new book, Flashlight Night.